Investigations into Pollution in the San Sebastian River

The containers analyzed by MARN presumably contain cyanide and ferrous sulfate

By Gloria Morán

Translation by Jan Morrill

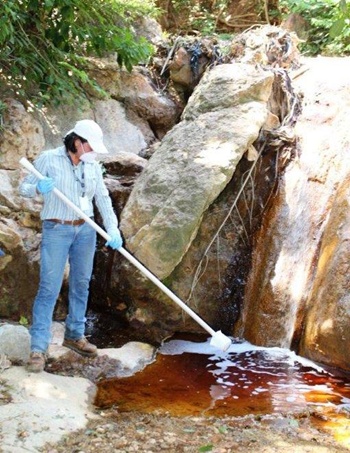

SAN SALVADOR – The color of the water seems to get worse as the current advances, beginning as an almost clear color until it becomes a strong brown color, which smells of rust and where the rocks which are immersed in the water also seem to have changed color over time. This is the reality for the San Sebastian River in La Union.

Pollution of rivers in El Salvador is well known, but this river in particular has caught the attention of environmental activists and, now, the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) because of the heavy metal contamination supposedly coming from the top of the San Sebastian Mountain, which used to be the site of mining operated by the multinational corporation Commerce Group since 1968.

However, according to a report presented by researcher Flaviano Bianchini, mining operations by other companies date back as far as 1904.

On the edge of the river there are a number of houses. Living there would be a pleasant experience if the pollution from the river weren’t such a dangerous contrast.

Also, close by one can find livestock animals, such as cows, chickens and pigs, all of which consume water from the river. The pigs freely bathe themselves in river water.

Some locals wash their clothes, their cooking utensils and drink water from this river, especially in the rainy season when the current hides the brown color of the water. They think, “if the water is clear, there is no pollution.”

The river accumulates all the acid mine drainage, especially the drainage washed down in the rainy season of metals leaching from the mountain, exactly where the mine was operating.

The Investigation

The MARN began its investigations after receiving complaints from the population which was concerned about the presence of containers holding high risk chemical substances near the top of the mountain.

There were two yellow containers, apparently new, that are secured by two locks on each container and around the containers there was a small brick wall. In one of the containers there were 23 barrels, presumably full of sodium cyanide and the other held black bags of ferrous sulfate, both of which are chemicals used in the gold extraction process.

The MARN took samples of both the chemicals found in the containers as well as the river water, within a perimeter of exactly 2.5 km of the San Sebastian River. The containers were open by staff from the Firefighters of La Union.

In spite of appearance that containers and even the locks had recently arrived, the person in charge of the site, who asked not to be identified, said that they have been there since 2009 and that they are the property of the Commerce Group, a company that brought them to the site with the hope of using them if the Government issued their permits to mine.

Roberto Avelar from the Office of Environmental Compliance of the MARN said he was not sure of the date when they will finish the investigation, but stated that when it’s over they will determine what to do with containers, what measures they will take regarding the river’s pollution and how to protect the lives of the locals.

Artisanal Mining

There is a narrow but long, humid and dark tunnel that is held up by small wooden beams. Young men who live in the town of San Sebastian work in this tunnel. There is not just one tunnel, but five more have also been counted.

Any human who enters in this tunnel and is not prepared for the humidity, the darkness and the lack of air won’t last five minutes before running in search of the exit.

One of the young men who work here said that the workers go in four or five times a day to bring out rock or soil that is then cleaned in an artisanal process to extract the gold. They are called “güiriceros” (which means a foragers).

Their tools are pickaxes, shovels, gas or battery operated lamps, a wheelbarrow, and the willingness to do a dangerous job without adequate safety measures.

There are four young men who aren’t more than 22 years old but no younger than 15 who work in this tunnel. Laughing and joking they said they are used to going in and out of the tunnel and that “we’re used to it.” They are aware of the danger but are not worried about it, this is their job, and that is how they survive.

The Procedure

In 2011 ContraPunto had the opportunity to witness the artisanal process for cleaning rock extracted for mining, and on that occasion a worker, who asked not to be identified, stated that buying soil and finding gold is like playing the lottery, because there are times when the process pays off and times when it doesn’t. He explained that there have been times when he has gone two years without finding any gold.

When the rock is given to workers who process the soil they go through the labor-intensive task of first pulverizing the dirt, which then is called clods. Then it is molded into balls the size of a baseball and which are put in the sun to dry.

The dirt is crushed in an artisanal grinder that is operated by a young man who spends more than five hours moving a double ended stick, that is “v” shaped allowing him to hold on to it, in circles. The lower part of the stick has a ball of cement attached that weighs about 150 pounds. This tool has a deep base where the soil is placed and this is how the work of pulverizing the soil begins.

When the balls of soil are dry, they are put in an oven where some chemicals in the soil are burned off. According to the worker who does the processing, this is to improve the clods and find more gold.

After the oven, the balls are placed again in the grinder where they are mixed with water and mercury, the chemical that separates the gold from other elements. “Even though the mercury leaves the gold white, once it is put in the oven it takes on a lovely color because it is pure 24 karat gold,” said the worker.

He also stated that artisanal mining incurs less risk than industrial mining, because even though the workers have a safety protocol, the toxic emissions from the chemicals they use are much stronger and more dangerous because they work at greater depths within the mountain, apparently around 400 meters deep.

The artisanal mining that is currently operating in the area would still entail risks, but to a lesser degree, due to the fact that this activity does not use chemicals, like cyanide, and would not cause large scale pollution of the environment nor humans.